National scaling

Combining detailed reference data with local socio-economic information reveal how the size, shape, and needs of the revolving door cohort vary across England.

Predicting interventions with the greatest impact

This approach allows predictions for different local authorities, highlighting where interventions could have the greatest impact. The analysis shows this cohort accounts for around 5% of the £23 billion the UK spends on reoffending, likely an underestimate.

Scaling the cohort across England

To align with the cost methodology, cohorts were grouped by crime type, defining the “revolving door” group as individuals who committed five or more offences over two years. This allowed for a realistic reflection of total offending, recognising that individuals may appear in multiple offence groups. The cost modelling was then applied at local authority level—using Medway, Maidstone, Canterbury and Thanet in Kent as reference points—to produce both upper and lower bounds of cohort size and cost benefit.

The reference cohort sizes and the multiplier factors are used in the calculation:

Understanding the calculations

The projections also help to surface outliers – areas where cohort size is significantly higher or lower than population alone would suggest. These exceptions prompt a deeper look at local context and system response, offering valuable clues about what drives demand and where targeted interventions could make the biggest difference.

The cost of the revolving door cohort

of crime

of crime

to crime

Cost of Crime Type

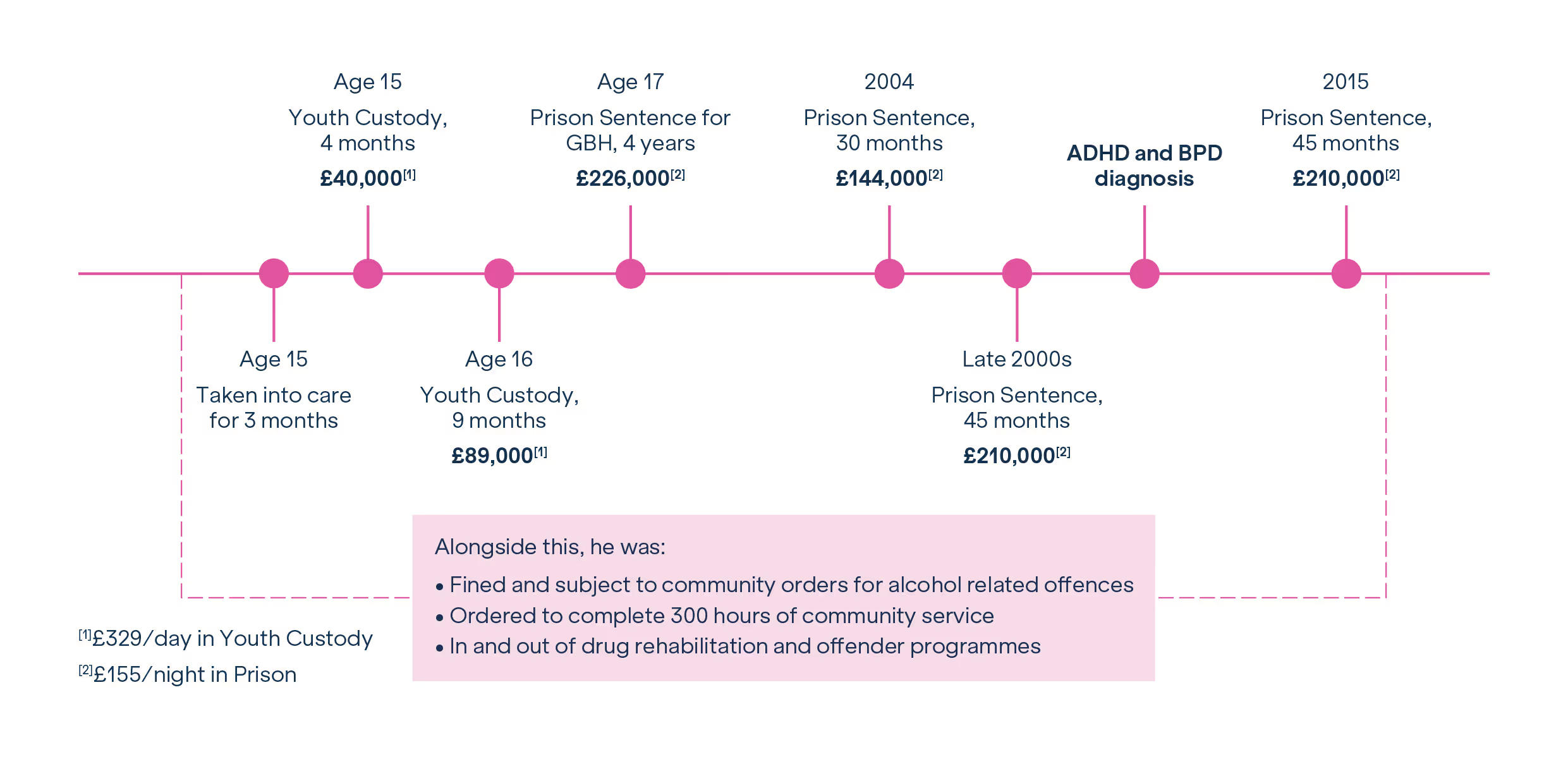

Individual User Journey: Costs and Insights

- Early vulnerability: First arrested at age 10 for criminal damage, escalating to armed robbery by 14. By 15, he had appeared in court five times.

- Fragmented support: Short-lived interventions included a youth liaison officer and brief psychological support. He was excluded from mainstream education and placed in alternative provision attached to probation services.

- Custodial history: Entered local authority care for three months at an estimated cost of £450,000, then multiple youth detention periods, including a four-year sentence for GBH. Later, he served three further prison terms between 30 and 45 months.

- Late intervention: ADHD and Borderline Personality Disorder were only diagnosed and treated in 2010.

- Supported accommodation: Provided between 2017–2019 at a cost of at least £60,000 over two years.

- Lifetime public cost: Conservative estimate exceeds £1.4 million.

Every court appearance, custodial sentence, and breach represents a missed opportunity to address underlying needs. This individual’s journey is not unique – it mirrors national patterns seen across the revolving door cohort. The case underscores the value of early, targeted, place-based interventions and joined-up data, showing how timely support can prevent escalation, reduce reoffending, and deliver both economic and human benefits.

Estimating the national socio-economic cost of reoffending

- Violence with Injury (ABH, GBH, and Assault Against an Emergency Worker)

- Shoplifting

- Drug Offences

- Criminal Damage

These categories were chosen for their prevalence in the reference cohort and the robustness of the data. The analysis focuses on individuals who have committed these offences, aggregating cohort sizes across four local authorities and using the average to scale the estimates nationally.

Cost impact

The revolving door cohort currently accounts for around 5% of the £23 billion the UK spends on reoffending each year - but this is likely a significant underestimate. Accounting for unrecorded crimes, additional offence types, and hidden activity such as repeated shoplifting (which can occur up to 16 times before being recorded), the true cost could be up to £4 billion higher. This means the cohort could represent as much as 23% of the total national cost of reoffending, highlighting the scale of the hidden burden on public services.

The implications are profound. This cohort places repeated strain on police, courts, probation, health, and housing services, while the human impact is equally significant. Many individuals face compounding vulnerabilities, including homelessness, mental health issues, substance misuse, and trauma. Each return to custody or court represents a missed opportunity for early intervention. Proactively identifying and supporting this group could relieve pressure on the system while delivering meaningful outcomes for individuals and communities, demonstrating both the challenge and the potential for transformation.

Useful links

Findings from 20 in-depth interviews with people who have lived through the revolving door of crisis and crime.

Advanced analysis reveals the patterns, unmet needs, and risks driving the revolving door cohort, showing how data can inform smarter, preventative interventions.

Research revealed clear patterns in the lives of people caught in the revolving door of crime, reflected both in the 20 interviews and in service data.

Read more about the research process, key findings, and expert recommendations.